“When you’re using, it’s kind of a lonely thing,” Holly began, her words trailing off into a mix of memories. On a breezy, sunlit day in March 2024, Holly sat outside the Sierra College Rocklin campus library on the veranda for an interview with members of this year’s California Humanities Emerging Journalists team.

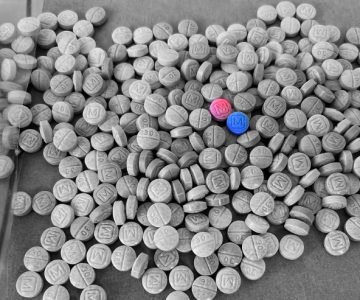

The team chose to focus on the impact of fentanyl, a powerful opioid, in our community. “Holly,” whose name has been changed to protect her identity, agreed to be interviewed for the project. The team felt it was important to include a point of view from a person who had experience as a user of these kinds of drugs over time, and with life in recovery.

Dressed in jeans and an affordable but well-kept blouse and blazer, Holly’s a youthful-looking 49-year-old Californian with long brown hair and a penchant for 80’s alternative music. She lives in a quaint 1,500-square-foot house on a quiet cul-de-sac in the greater Sacramento area with her boyfriend, two cats, and a dog. Her easy laughter while discussing her past concealed a heartbreaking history.

“I didn’t have much of a life,” Holly said of her days living with addiction, adding that “it was mainly just focused on trying to get money so I can try to get prescriptions, so I can get pills.”

A Dentist for Depression

Holly’s opioid addiction began while living in Florida. At 29, a seemingly routine visit to her dentist for tooth pain changed her life forever. “I went to the dentist and got a prescription for pain pills.” Holly’s dentist gave her Dilaudid, a powerful opioid typically reserved for severe pain management when other treatments fail. Despite the potency of the pills, Holly didn’t abuse them right away. “I took them as prescribed,” she said. “I had a friend that came over and said, ‘oh, do you have any pain pills?’” Holly explained that her friend sold her on the idea that taking the pills recreationally would be fun.

Holly found that the pills had a deeper impact on her. “I was always kind of depressed,” Holly said, adding that when taking the pills, “they made me feel not depressed. And so then that’s how it started.“

Holly singled out her mother as a source of her addiction struggles. “My mom is kind of the root of my troubles,” she said. Her mother “abandoned my brother and I when we were young and was never there for us.” Holly concluded that her mother “was off doing her own crazy things.”

As Holly’s recreational opioid use continued, her addiction deepened. “I ended up meeting a boyfriend and lived with him and his parents,” she said. While Holly described the family as very kind, they put their foot down regarding her ongoing drug abuse. “His parents said, ‘hey, you can’t stay here forever. You need to go back to your family,’” Holly recalled.

Unfortunately, Holly’s years of drug abuse had already burned bridges with much of her family. “I called my dad and my brother and said, ‘hey, can I come back with you guys,’” but Holly was rebuffed. “My brother and my dad were like, no, don’t come here. And I was like, ohh, they’re jerks.”

Faced with homelessness, Holly turned to her last resort. “I was thinking, oh boy, I have nowhere to go. So then I thought, well, my last choice is my mom.”

Like Mother, Like Daughter

Holly moved in with her mother and stepdad in Oregon, but found her mother struggling with addictions of her own. “She was using, like, Ritalin and Adderall and crushing it up and snorting it like it was speed,” Holly said, adding that it complicated her own struggles. “Looking back, that was awful for me to go live with my mom because she was just letting me use. That wasn’t helping me get sober.”

“I went from bad to worse,” Holly concluded.

When Holly moved to Oregon, her opioid addiction became all-encompassing. She found any way she could to get her hands on pills to avoid withdrawal and cope with deep-seated emotional issues.

“I didn’t have much of a life. It was only focused on not being sick and not being depressed,”

Holly said, adding that if she wasn’t taking pills, she was stressed and sick.

Holly’s life became focused on getting pills. “I was just doing little odd jobs and doing pills, and collecting food stamps, or doing side hustles or whatever for money,” she said. She also escalated her opioid abuse, moving on from Dilaudid to Oxycontin, and eventually methadone.

When working for pill money wasn’t enough, Holly took things a step further. “I would lie for pills [to be] prescribed to me,” Holly said, describing her frequent doctor visits, also known as doctor shopping. “I had this mysterious back pain that doctors would just believe me and prescribe me things.” Holly continued, “I was like, ‘oh I don’t have insurance, so you can’t do a CT scan’ so they would give me Valium and fentanyl.”

Holly’s commitment to getting pills eventually led to additional consequences. While employed as a part-time caretaker for the elderly and disabled, Holly landed in legal trouble. She explained that the patient she was caring for “was addicted to pills, so sometimes she would give me a pill here and there.” The occasional pill didn’t suffice, so Holly stole ten of them. “She called the cops on me… so I had to go to jail for a week,” Holly recounted.

The short-term impact of Holly’s incarceration was relatively minimal due to another toothache. “I had a prescription for Vicodin so in jail, once a day they were giving me Vicodin, so I didn’t detox in jail,” Holly explained. Longer term, it resulted in her having a felony on her criminal record.

Hints of Recovery

Once out of jail, Holly began seriously considering getting clean, something her family encouraged. Her aunt facilitated Holly’s admission to an exclusive recovery center in Southern California, at no cost. Her stepdad, who was on dialysis and deathly ill at the time, urged Holly to accept the offer. “The last week he was alive, he said ‘I want you to leave here and go to rehab … please go, just please go and get out of here,’” Holly recalled.

Although she agreed to go, the morning she left for rehab, Holly’s stepfather died, which caused her to question her motivation. “I wasn’t really ready, I was just kind of going because I was thinking, oh I’m fulfilling his dying wish and I’m here now and I was just so confused,” she said.

Holly’s 2008 rehab visit did not result in the hoped-for recovery. “I think it was about 35 days. I did the detox, and I really wasn’t ready, and I was just so angry, and I ended up leaving with a guy,” Holly said. “I wasn’t ready and I wasn’t appreciative. I just wanted to get out and keep using. I didn’t care about myself and wanted to get out of there. So yeah, I ended up leaving.”

The weight of life’s post-rehab responsibilities felt crushing to Holly. She said, “what am I going to do after [rehab]? Get an apartment by myself? I just thought, I’m not going to be able to do that. How am I gonna get an apartment by myself? I don’t even have a job … It’s just too hard.” Holly didn’t want to go back to her mom’s because of the continued drug use in the home. “Where else am I going to go? There’s nowhere else for me to go that’s healthy,” she added.

Within a matter of weeks, though, Holly return to Oregon and settled into a pattern of drug abuse alongside her mother. “It was easier than being sober and thinking about my issues and having a real job, and paying taxes, and paying rent,” she explained. At the time, Holly said living life sober seemed “just so much harder.”

Sibling Salvation

Holly stayed in a drug-fueled limbo with her mother until 2013, when she received a call from her brother in Sacramento, whom she had been estranged from for several years. He and his wife had just had a baby, and he invited her to move in with them, at his wife’s urging. Holly recalled the moment, saying, “it was so exciting, like, oh, gosh, I can finally get sober in a healthy environment because they don’t do drugs or smoke or drink. They have a new baby and I can be around a healthy environment.”

Reflecting on her decision to leave Oregon, Holly said, “I wish every addict could be given that opportunity, you know, to be taken out of an unhealthy situation and be put in a healthy situation.”

Holly’s life of recovery since 2013 has been marked by both challenges and triumphs. She described getting her first steady job in over a decade, noting, “working at McDonald’s at my age was embarrassing, but whatever because I had a felony on my [record].” Subsequent retail jobs and the support of her family, who helped her get her criminal record expunged, were crucial steps in rebuilding her life Holly said.

While Holly has had relapses since moving back to California, they’ve been short-lived. Yet, the fear of a full-blown descent back into drugs looms. In 2017, Holly’s sobriety was tested when her dad passed away suddenly. “My dad died … and I thought, ‘Oh my God, how am I gonna get through this without doing pills?’ It was awful,” she recalled.

Just weeks after her father’s death, Holly faced another challenge to her sobriety, this time due to an accident at home. “I fell on my arm and my shoulder dislocated, and I was trying to pop it back in and I couldn’t” she recounted. Her sister-in-law guided her to the ambulance and told the paramedics Holly was in recovery. “My sister-in-law was following us and she’s like, ‘she’s an addict don’t give her anything,’” Holly said. “I was like what? Oh my God, cause I just wanted some pain medicine … I was like ‘this is real,’ I was gonna kill her!” she concluded with a boisterous laugh.

At the hospital, Holly received pain medication for her injury, but found no such relief at home. “I went home, I didn’t have any pain meds. I healed. It was awful,” she added with a subdued chuckle.

Recovery Takes Root

The path to recovery is as varied as those who travel it. In the years since moving back to California, Holly’s almost ten years of sobriety have been marked by an absence of drug rehabilitation centers and only a handful of Narcotics Anonymous meetings. Instead, she’s leaned heavily on family and doing her best to avoid temptation.

As Holly explained, though, it’s far from perfect. “I’m still trying to find healthy coping strategies all these years later,” she said. She developed severe anxiety since getting sober, and said “while I may not be using pills anymore, I often turn to other things to help me feel better if I’m feeling down or stressed. Food, shopping, [and] spending money I don’t have.”

Holly said she understands what’s at stake, “I try to escape my stresses sometimes … I have to try so hard to be mindful that that’s what’s happening because if not, it can lead to a relapse.” She concluded, “it will be a fight for the rest of my life.”

“Without my brother and sister-in-law, I don’t know where I’d be today,” Holly said of the support she received in getting sober. “They took a chance on me,” she added. Holly also expressed something approaching appreciation for her brother and dad’s refusal to allow her to move in all those years ago. “My dad and my brother cutting me off was the best thing for me because then it was kind of forcing me to get sober.”

Recently, Holly started a new job at a respected and well-paying Sacramento-area company. She spends her free time bike riding, working in her yard, and spending time with her niece and nephew. Holly even maintains a relationship with her mother in Oregon, thanks to distance and Holly’s growing independence.

When asked if she had advice for anyone on their own path to recovery, Holly said, “it takes many years. It just doesn’t take 30 days in rehab.” She added, “the first step; you have to go through withdrawal. Take the first steps. So it’s not just rehab and then all of a sudden you’re fixed. It’s something that you’re always having to work on.”

Holly lightheartedly concluded the interview with a chuckle and another quick piece of advice, “don’t use drugs!”

Written and Reported by Greg Micek | Interviewed by Jeralynn Querubin and Greg Micek

Editor’s Note

“Seeds of Addiction, Roots of Recovery,” is one in a set of stories on fentanyl in our community. See also “Harm Reduction: Support, not Stigma” by Miranda Ricks and “Law and Order or a Gentle Touch? County Neighbors Fight Fentanyl” by Greg Micek.

These stories were supported through the California Humanities “Emerging Journalist Fellowship program.” The program awards student-fellows in journalism programs at California Community Colleges support to do community-based journalism, work with a faculty adviser, and participate in a statewide cohort. 2024 is the third year that the Sierra College journalism program has been awarded this significant statewide grant.

For more information, visit www.calhum.org. Any views or findings expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of California Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.