Over the past decade, the fentanyl epidemic has emerged as a critical public health crisis in the United States. According to USAFacts.org, overdoses from the drug have claimed over 330,000 lives since 2012, devastating communities large and small in the process. In Northern California, the powerful synthetic opioid’s impact has been acutely felt in Placer and Nevada counties. Despite their similarities, the county neighbors have adopted markedly different approaches to combat the life-or-death crisis.

Placer County’s fentanyl strategy is reminiscent of the 1980s. A law enforcement-led approach paired with a catchy anti-drug tagline. Nevada County, in contrast, has taken a “touchy-feely” approach. Providing easy access to resources that help make illicit drug-use safer.

While both characterizations have elements of truth, the reality is more nuanced. To understand why Placer and Nevada counties have taken such divergent paths, it’s important to first understand fentanyl and its unique dangers.

Fentanyl’s Threat

Fentanyl is roughly 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and about 50 times stronger than heroin. Initially developed for pain management in cancer patients, the highly addictive drug is considered safe in clinical settings.

It’s the illicit production and distribution of fentanyl that has fueled the current public health crisis. According to the Center for Disease Control, it began in 2013, marking the third wave of America’s opioid epidemic. When fentanyl is produced in unregulated labs with minimal safety standards, the unpredictable quality, combined with the drug’s potency, dramatically increases the risk of overdose.

There have been recent bright spots in the fight against fentanyl. Overdose deaths decreased nationally for the first time in 2023. In spite of that positive sign, in 2023 alone, nearly 75,000 people in the US died from fentanyl overdoses. It is still considered the leading cause of death for people between the ages of 18 and 45.

The lethality of illicit fentanyl is largely attributed to the drug’s widespread availability and frequent presence in counterfeit versions of other drugs. For example, individuals using methamphetamine, street versions of painkillers, or even Xanax can unwittingly buy fentanyl spiked drugs with few reliable ways of verifying their safety.

California’s Numbers

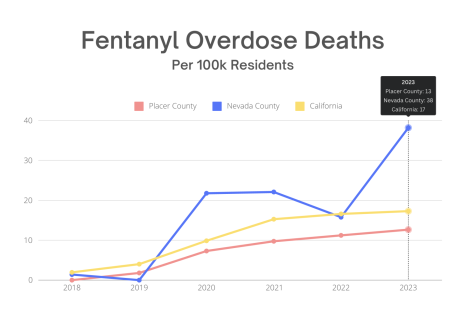

The California Department of Public Health’s Overdose Surveillance Dashboard illustrates the impact fentanyl has had across the state since arriving in a deadly wave in early 2020. Age-adjusted fentanyl deaths per 100,000 California residents rose from 6.65 during the 12 months ending in Q2 2020 to 17.92 during the 12 months ending in Q3 2023—a 169% increase.

The politically middle-of-the-road rural community of Nevada County, which includes the cities of Grass Valley, Nevada City, and Truckee, experienced an increase as well. During the 12 months ending in Q2 2020, the county reported 8.18 fentanyl-related deaths per 100,000 residents. By the 12 months ending in Q3 2023, that number had jumped to 33.69 fentanyl-related deaths per 100,000 residents, marking a heartbreaking 312% jump.

Placer County, known for its conservative politics and suburban communities of Rocklin and Roseville, also encompasses a significant rural population along Interstate 80 to the Nevada border. The county saw an increase in fentanyl-related deaths from 5.04 per 100,000 residents during the 12 months ending in Q2 2020 to 12.27 per 100,000 residents by the 12 months ending in Q3 2023—a 143% increase.

Law & Order in Placer County

Placer County’s approach to tackling the fentanyl crisis is evident from a simple Google search of the phrase “Placer County fentanyl.” The search results almost exclusively feature links related to the county’s district attorney’s office, highlighting the central role of law enforcement in their abstinence based law & order strategy.

The county’s anti-fentanyl efforts are prominently displayed on a dedicated webpage from the district attorney’s office titled Fighting Fentanyl in Placer County. The site reads as a warning to anyone considering getting involved with fentanyl, whether as a dealer or user. A full-screen poster warns viewers that selling fentanyl in the county may result in a murder charge. Alongside it, there are updates on cases brought against alleged fentanyl dealers.

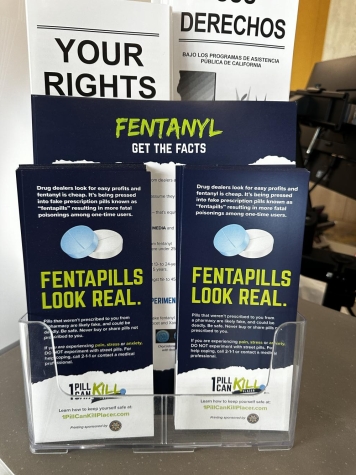

Additionally, the page links to the “One Pill Can Kill Placer” website, a prominent component of Placer County’s fentanyl abuse prevention efforts. This DEA initiative, launched in 2021, provides local governments and schools with a ready-made package to raise awareness about the dangers of counterfeit pills.

At first glance, One Pill Can Kill seems to be a rhyming rehash of Just Say No. The well-known, and much derided, anti-drug initiative is familiar to anyone who lived through the 1980s.

In an April 2024 phone interview, Placer County’s District Attorney, Morgan Gire, refuted the comparison. “I remember Nancy Reagan getting up there and saying that. And I say all the time, this is not just a retread of Just Say No.” Gire emphasized that the current campaign is fundamentally different as it focuses on life-or-death consequences instead of lifestyle choices. “This will kill you within minutes, potentially the first time you try it,” he warned.

Placer County spent $1 million-plus on their One Pill Can Kill campaign. The money went towards parent-teacher informational nights, town halls, as well as widespread billboard ads, bus wraps, and social media campaigns.

The aim of the campaign was to spread the message about the dangers of fentanyl, with a particular focus on children and their parents, according to Gire. He added that “…every high school in Placer County, over 30,000 students,” has gone through the county’s fentanyl awareness campaign.

“Fentanyl has really changed the landscape. I’ve been a narcotics prosecutor for 25 years, and fentanyl’s lethality is unprecedented,”

Gire stated, underscoring the uniqueness of the fentanyl epidemic. “Someone addicted to methamphetamine or heroin might eventually succumb without treatment, but with fentanyl, a single use can be fatal. It’s a roll of the dice,” he concluded pointedly.

Robert Oldham, Placer County’s Director of Health & Human Services, echoed Gire’s warning regarding fentanyl’s lethality during an April, 2024, Microsoft Teams interview. He said that overdose victims in Placer County are “people who really don’t have a lot of history using illicit drugs.” Instead, Oldham said they’re “younger people, but also older people who are sharing pills.” His observation fits the seemingly broad 18-45 year old victim age demographic of fentanyl overdoses.

Oldham warned that many young victims who die from fentanyl overdoses don’t display the typical warning signs associated with drug abuse. They don’t always display sudden changes in their behavior, social groups, or overall personality. He said that overdose victims are “…sometimes people who were just using for the first time, recreationally.”

Oldham emphasized the importance of community-wide efforts like One Pill Can Kill in addressing the fentanyl crisis. “Our campaign brought us together across different departments within the county and with many non-governmental partners,” he said. “We have seen a lot of positive things, as well as our ability to come together on this critical issue.”

From an enforcement standpoint, Placer County has garnered national attention for Gire’s vocal stance on prosecuting drug dealers for overdose deaths. “It is a public health crisis, but is also very much a public safety crisis. You have to handle both of those crises together,” Gire said.

Despite the punitive messaging on the Fighting Fentanyl in Placer County website, Gire denied that his office is being overly aggressive. He noted that enforcement is just one part of their broader strategy. Gire said:

“We’re not going to arrest and prosecute our way out of this crisis, but holding dealers accountable is necessary.”

He added that while the county has seen over 200 fentanyl-related deaths, his office has filed charges in very few cases- just five, according to the Fighting Fentanyl website. “This shows we’re using this approach sparingly and appropriately,” Gire concluded.

While Placer County prosecutors were among the first in the US to charge dealers with murder in fentanyl overdose deaths, they’re no longer the outliers. In recent months, several other counties in California have charged dealers with fentanyl-related deaths, including those in more politically liberal areas. For example, in May 2024, San Mateo prosecutors charged a man with murder for selling drugs to a woman who died of a fentanyl overdose. Nationally, murder charges against dealers have become more common as law enforcement seeks accountability for overdose deaths.

Nevada County’s Gentle Touch

In contrast to Placer County’s prevention and prosecution stance, Nevada County has adopted a more community-centric harm reduction approach to fentanyl. A Google search for “Nevada County Fentanyl” brings up resources like the 988 crisis hotline and harm reduction services. Notably, the county’s Fentanyl and Opioid Overdose Prevention website is managed by their Public Health department rather than the District Attorney’s office.

Nevada County’s overdose prevention website focuses almost entirely on providing harm reduction resources and education. Including Narcan (naloxone) distribution, fentanyl test kits, and safe drug use practices. A complete contrast to Placer County’s large-font messaging and enforcement-heavy warnings.

Instead of adopting the DEA’s One Pill Can Kill campaign, Nevada County has its own initiative, Know Overdose Nevada County. This site forgoes anti-drug messaging in favor of a list of goals, including “Prevent deaths from drug overdoses” and “Keep people safer when using drugs.” The emphasis is less on preventing drug use and more on promoting safe drug use practices.

The origins of the Know Overdose campaign in Nevada County and the One Pill Can Kill campaign in Placer County further emphasize their differences. One Pill Can Kill is a result of the DEA’s national campaign. On the other hand, over 30 local organizations, including hospitals, businesses, and nonprofits, are behind Nevada County’s Know Overdose.

Another differentiator? The logo and other campaign materials for the Know Overdose Nevada County initiative were created by Design Action Collective, a business based in the East Bay that describes itself as a “worker-owned, anti-capitalist design firm serving movements for liberation since 2002.” The DEA it is not.

Toby Guevin, the Health & Wellness Program Manager for Nevada County, shared additional details about the origins of Know Overdose during an in-person interview in April, 2024. “In March of 2020, when fentanyl first arrived in Nevada County, we saw a dramatic increase in overdoses and deaths,” Guevin recalled. “Over the next 10 months, we had 19 overdose deaths involving fentanyl, effectively doubling our overdose death rate.”

In response, a group of community members and public health officials came together to address the crisis. “We immediately increased the distribution of naloxone, or Narcan, and started educational presentations about opioid use, naloxone administration, and fentanyl test strips,” Guevin said. He added that electorate support for the liberal distribution program has been strong, with significant engagement from the community.

Guevin touted the extensive nature of Nevada County’s naloxone training and distribution efforts. “In 2023, we conducted 99 trainings and trained over 2,300 residents,” he noted. “We’ve built community capacity to distribute naloxone with over 20 organizations and businesses now serving as naloxone distributors.”

Although he did not address Placer County’s approach directly, Guevin expressed skepticism with overly-aggressive messaging. “I think what we’ve learned in terms of evidence-based approaches is that fear tactics don’t always work.” Guevin continued:

“For us, it’s important to reduce stigma and judgment and provide accurate, evidence-based information about the health consequences of drug use.”

Nevada County’s approach emphasizes building trust and relationships within the community, according to Guevin. “When you build trust with folks, they are more likely to reach out if they have questions or need help,” he said. Guevin explained that the objective in Nevada County differs from others. “Our goal is to provide information without judgment, allowing people to make informed decisions about their health and safety.”

Guevin emphasized the need to be supportive in order to help save lives. “Stigma and judgment keep people from reaching out or using naloxone. We want to make sure people feel comfortable accessing resources and using them,” he said.

“Our message is that everyone deserves to be safe and cared for, regardless of their drug use.”

Part of Nevada County’s harm reduction approach involves promoting the use of and providing fentanyl test strips, which can help users identify the presence of fentanyl in their drugs. Guevin explained, “while they’re not a panacea, they are an important tool in our harm reduction efforts.”

One relatively unique aspect of Nevada County’s fentanyl strategy is the use of vending machines to distribute harm reduction supplies. “We have vending machines across the county that provide free naloxone and fentanyl test strips,” Guevin said of the county’s three vending machines. “This ensures that people have access to these life-saving tools whenever they need them,” he added. Harm reduction vending machines are still somewhat uncommon in California, but are gaining popularity across the country.

Aside from vending machines, a number of local partners actively support Nevada County’s harm reduction plan by actively distributing supplies.

One of those, local grocery chain BriarPatch Food Co-Op, provides free Narcan at its customer service desk to anyone who asks. During a June 2024 visit, getting a free two-pack of Narcan was as simple as asking the employee. There was no cost, no questions, and no need to make a purchase at the store. It was more convenient than asking for the bathroom key at a gas station.

Guevin summarized Nevada County’s fentanyl overdose strategy when he said, “our goal is to keep people alive and support them in seeking treatment when they are ready.” He added, “we know that there’s been hundreds of people’s lives that have been saved because naloxone is readily available in the community.”

Nobody’s Right, if Everybody’s Wrong

The differences in how Placer and Nevada counties are tackling the fentanyl crisis are clear. Placer County’s strategy focuses on abstinence education and law enforcement. Nevada County, on the other hand, relies on harm reduction and reducing the stigma associated with drug use to encourage users to seek help.

Placer County’s abstinence approach, characterized by the One Pill Can Kill campaign and highly publicized prosecution of dealers, reflects a belief in strong deterrents and widespread awareness. This strategy is focused on preventing drug use by amplifying the potential repercussions. It stresses that drugs aren’t worth the risk.

Conversely, Nevada County’s Know Overdose harm reduction approach emphasizes community education and widespread resource availability. Their strategy is built on creating an environment of comfort that’s free of judgment for users, with the hope that they’ll live long enough to seek help with recovery. The aim is to keep people alive, regardless of their path.

Both approaches have their shortcomings and merit criticism. Abstinence-centered education presumes that people will listen to authority figures’ advice on what’s best for them. It fails to prepare them for the possibility that they, or a friend, may use drugs anyway.

A criticism of the harm reduction approach suggests that it normalizes the risky behavior of illicit drug use. That it focuses solely on safe drug use rather than providing the tools to avoid them altogether.

Which strategy is most effective? It’s both.

A September 2023 Department of Health and Human Services CDC report on unintentional drug overdose deaths provides some answers. A combined approach, according to the report, could lower overdose deaths. It recommended education and trainings that deliver an abstinence-style message against taking illicit and non-prescribed pills. It also recommended harm reduction messaging that encourages drug testing and Narcan.

Neighborly Nuance

Californians have numerous options for drug prevention and harm reduction resources. Notably, the California Department of Public Health’s Overdose Prevention Initiative (OPI) provides services for both abstinence and harm reduction strategies. However, at the local level, both Placer and Nevada County appear to fall short of such a combined approach.

Placer County’s abstinence-centered One Pill Can Kill website contains little information on harm reduction. Buried within the site is a small section explaining what Narcan is and where to find it. The site provides no information regarding cost but lists five locations in Placer County (and one in Nevada County) where it can be found.

Calls to each of the Narcan resources listed met with mixed results. One location only allowed the caller to leave a voicemail, while others eventually offered the option of speaking to an operator. They indicated that Narcan was available for free; simply ask reception for some, and a counselor will come speak to you before handing it over.

Additionally, Placer County’s One Pill Can Kill website instructs users to “always call 911 before administering Naloxone as medical attention may still be required to prevent further harm.” This advice conflicts with guidelines from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), as well as the instructions provided with Narcan. Both instruct users to administer a dose prior to calling 911. This seemingly minor distinction could be critical when dealing with an overdose. Any delay in administering Narcan due to waiting for a 911 operator could prove fatal, whereas Narcan is safe for those not experiencing an overdose.

Nevada County’s most public online resources, such as Know Overdose Nevada County, and their Public Health Department’s Drug Use Prevention page, contain little information on drug abstinence. Resources to help parents discuss the dangers of drugs with children, or signs to look out for that someone is using drugs, or is at risk of doing so are also absent. The message is entirely harm reduction-focused.

Despite these differences, there are notable similarities in their efforts. Both Placer and Nevada County programs illustrate the value of community involvement and easy access to resources and information. They also show a commitment to education and awareness, utilizing various media and outreach efforts to inform the public about the potential dangers of fentanyl.

The question remains whether Placer and Nevada counties can more effectively co-opt and share strategies for the betterment of their communities. Stepping outside their respective lanes to adopt more balanced approaches could prove beneficial to everyone. After all, what’s most important is that individuals struggling with substance abuse, or at risk of falling into its temptations, have access to support and resources, regardless of the approach their local government takes.

Written, Reported, and Visuals by Greg Micek

Editor’s Note

“Law and Order or a Gentle Touch? County Neighbors Fight Fentanyl” by Greg Micek is one in a set of stories on the topic. See also Micek’s “Seeds of Addiction, Roots of Recovery,” and Miranda Ricks’ “Harm Reduction: Support, not Stigma.”

These stories were supported through the California Humanities “Emerging Journalist Fellowship program.” The program awards student-fellows in journalism programs at California Community Colleges support to do community-based journalism, work with a faculty adviser, and participate in a statewide cohort. 2024 is the third year that the Sierra College journalism program has been awarded this significant statewide grant.

For more information, visit www.calhum.org. Any views or findings expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of California Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.