The Old Auburn Cemetery is exactly what it sounds like; tucked between bustling streets and across from the train station, it houses hundred-year-old graves and tall, shadowing trees. I walk along the paths, thinking to myself that this look is what might attract random Auburn teenagers with nothing else to do to the spot. At least, it did for my friend and I, when we were in high school. I remember the summer air rustling leaves as we imagined ghosts behind our backs. Now, I’m making a return visit alone on a rainy day to investigate the grave of a person who seemed almost fictional. An engraving in the stone reads, “Fatally wounded in a gun duel with the law, July 11, 1859.” These words opened up to me the story of Rattlesnake Dick.

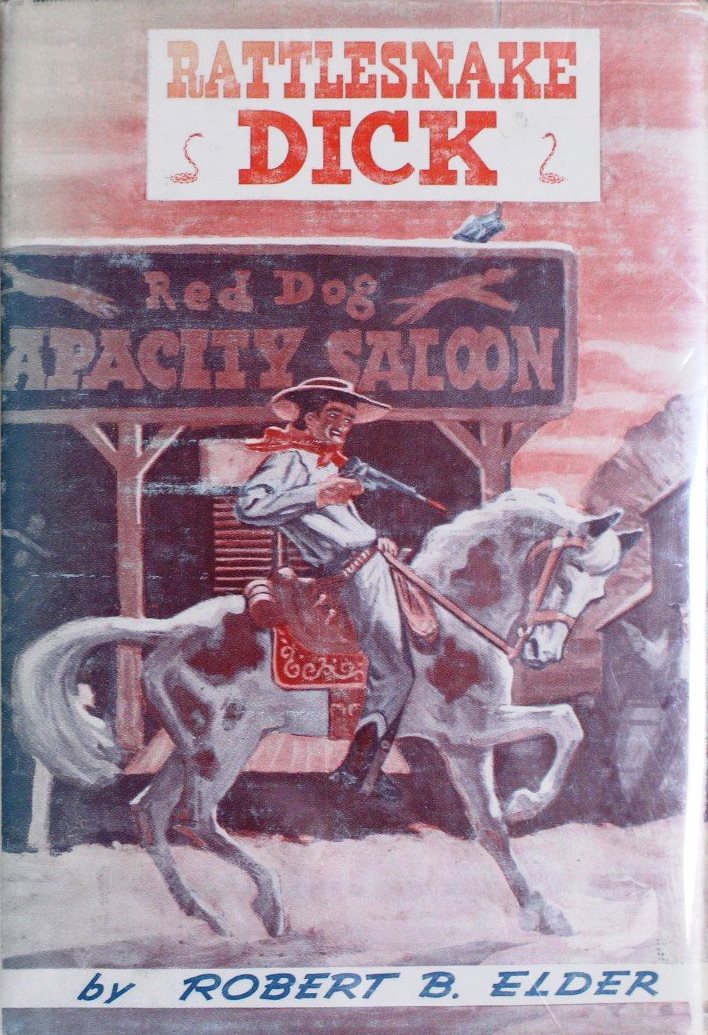

A household name for many locals of Placer County, Rattlesnake Dick has been considered one of the most notorious outlaws of the West. Throughout the 1850s, the Canadian-born miner-turned-thief and his gang were known criminals, meeting their end in a shootout in Auburn. Yet the circumstances which built his pathway to crime are often not as well known as the more dramatic parts of his life.

Richard H. Barter, aka Rattlesnake Dick, came to the west with no plans for a life of crime. According to a newsletter for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), he and his brother planned to mine for gold in the American River and use the money to support their sister, who remained in Canada. Yet after a false accusation of thievery from a fellow miner, Barter was sentenced to two years at San Quentin. After his innocence was confirmed, Barter was released, but he couldn’t shake his undeserved reputation as a criminal. This taint on his name, coupled with his formed connections from the time he served in prison, made it possible for Richard H. Barter to become Rattlesnake Dick.

The events of Barter’s life occurred more than a century ago. But the circumstances under which he turned to a life of crime are still relevant today. Statistics from the Office of Justice Programs show that 68 percent of released prisoners will be arrested again within three years. And it seems that the prison system plays a factor in this return to crime. In an article from Corrections Today, it is explained that “longer prison stays inevitably lead to the break-up of family and community ties and to the deep absorption of prison culture and values.” Here it can be seen that extended exposure to life in jail increases the likelihood of repeated criminal activity.

Barter accepted his title of “Rattlesnake Dick” and all it insinuated when word got out of his history in Shasta County. The Sacramento Bee describes his entry into crime: “Depressed about his failed reputation, he held up someone for $400. He went on to form gangs and terrorize the Sierra Foothills from Nevada City to Folsom.” Barter had the means to form a group of outlaws from his time in San Quentin, and so he teamed up with the notorious Tom Bell. Rattlesnake Dick’s story begins and ends with Placer County; in 1859, he came across a posse of Auburn officials and engaged in gunfire with them. Wounded, he rode off, and the next day his body was found, with three bullet holes, including one in the head. The identity of the person to have shot the final blow remains unclear to this day. Barter was only twenty-six years old.

Rattlesnake Dick has served as a local legend for decades, a caricature of the West in its heyday. His grave appears to be hardly weathered; it is large, recounts the details of his death, and is surrounded by the graves of other prominent historical figures of Auburn. His story is a reminder not only of the lawlessness of his era, but of the conditions which produced such lawlessness. In many ways, Richard H. Barter was thrusted into an unfavorable spotlight and was left to his own devices. A letter from his sister, which was found on his body after his death, reads, “(God) knows there is a secret wish (within you) to be a better man.” Perhaps there is some truth to this hope, but Barter remained a wanted man until the very end.

Written by Olivia Joyce | Photography courtesy of Chapman & Grimes